The Royal Yoga: A Path to Freedom

According to Patañjali’s Yoga Sutra, the classical text on yoga, the purpose of yoga is to lead to a silence of the mind (1.2). This silence is a necessary condition for the mind to be able to accurately reflect objective reality without introducing its own subjective distortions. Yoga does not create this reality, which is above the mind, but only prepares the mind to apprehend it by assisting in the transformation of the mind. from an ordinary mind—full of noise, like a whole army of frenzied and drunken monkeys—to a still mind.

This transformation is not brought about by any effort or practice, as the Yoga Sutra (4.2–3) reminds us, for it is an unfolding of nature’s own potential tendency. The practice and discipline are necessary only for removing the obstacles to this unfolding, just as a gardener removes the weeds for the sake of a healthy crop. The attempt to eliminate the obstacles to the natural unfolding and development of the human being is made through yoga, and this attempt is made so that the person’s true and real nature may be realized. This real nature is independent of the contingent conditioning of space-time, thought-feeling, fear-pleasure, and form-species. In other words, the real being, called purusha, is independent of all the forces and controls of prakriti, the realm of causality and nature, both subtle and gross. The real is above and behind the actual. The sole purpose not only of human incarnation but of the whole of prakriti, as the Yoga Sutra (2.21) tells us, is for the realization of purusha. Enlightenment and freedom are in this realization alone. Yoga is one of the six classical darshanas (perspectives, visions) for the attainment of ultimate reality. Out of these six schools of Indian philosophy, the school of Samkhya is often associated with yoga, and the two are frequently coupled together. There does not seem to be much basis for this association, for Yoga and Samkhya have represented two distinct approaches for a very long time, even though there are some similarities in their underlying cosmologies. On the other hand, all the schools of thought in India, even the ones opposed to Yoga in its metaphysical doctrines, such as the school of Vedanta, have recognized the great value of the practical aspects of yoga. Dating from a period prior to the ascendancy of the Aryans in India, yoga has had an enormous influence on all forms of Indian spirituality, including the Buddhist and Jain, and later on the Sufi and the Christian. Yoga can be said to constitute the very essence of practical spirituality of India.

The word 'yoga' is derived from the root yuj, which means to unite or to join together, much like the etymological meaning of the word 'religion'. The practice of yoga may lead to the union of the human and the divine within the self. It is a way to wholeness and to an integration of all aspects and levels of oneself. Yoga is not just a collection of certain practices devoid of a metaphysical basis, but it is based upon a perfectly structured and integrated worldview which aims at the transformation of a human being from the actual and unrefined form to a perfected form. The prakrita (literally ‘natural’, ‘common’, ‘vulgar’, ‘unrefined’) state is one in which a person compulsively repeats actions, in reaction to the forces of prakriti, which are active both outside and inside the person. Through yoga a person can become sanskrita (literally, ‘well made’, ‘well put together’, ‘refined’) and thus no longer be wholly at the mercy of natural forces and inclinations. It can be said that yoga leads to a freedom from nature, including the freedom from human nature; its aim is transcendence of human nature into pure being.

Yoga is concerned with being (sat) and knowing (jñana) as well as doing (karma), and therefore it cannot be classified exclusively as religion or science or art. The aim of yoga, however, is beyond these three and beyond any opposites they imply. Mythologically, Yoga is sometimes personified as the son of Dharma and Kriya. Dharma is essentially the order that is the support of the cosmos, and Kriya, as action and performance, is a shakti (energy, power) of Vishnu in one of his incarnations. The importance of yoga in the Indian tradition is obvious: a name or an epithet of Shiva is Yoganatha; of Vishnu, Yogapati; and of Krishna, Yogeshvara; in each case meaning essentially “the master or lord of Yoga.” Without the mastery of yoga, indeed, nothing can be accomplished rightly. As the Yogashikha Upanishad (1.67) says: “Verily there is no merit higher than Yoga, no good higher than Yoga, no subtlety higher than Yoga; there is nothing that is higher than Yoga.”

The Central Yoga

Although there are many kinds of yoga, such as karma yoga (the yoga of works) and bhakti yoga (the yoga of love), the Indian tradition has in general maintained that there is only one yoga, with varying emphases on different aspects and methods employed in various schools of yoga. The most authoritative text of classical yoga is the Yoga Sutra, Aphorisms of Yoga (abbreviated as YS), the compilation of which is attributed to Patañjali. Nothing very much is known about Patañjali, not even when he lived. It is possible that the Yoga Sutra text was compiled sometime between the second century BCE and the fourth century CE. In any case, there is no question that most of the ideas and practices mentioned in the Yoga Sutra were already familiar to the gurus (teachers) of Indian spirituality, who passed them on to their disciples with appropriate instructions and initiations. As is the mark of the sutra (literally, thread) literature, the Yoga Sutra presents the ideas in an extremely terse manner, leaving it to the individual teacher to expound the ideas more fully for a circle of disciples. In the process, no doubt each teacher emphasizes the aspects regarded as most useful.

The aim of yoga is set out in the beginning of the Yoga Sutra, in its most celebrated and most debated aphorism (1.2), namely, Yogah chittavritti nirodhah (Yoga is the removal of the fluctuations of consciousness). One practices yoga to steady the attention, which is constantly undergoing fluctuations (vritti). These fluctuations may be pleasant or unpleasant, but they are, in either case, distractions from the steady attention of a quiet mind. These vrittis are grouped under five headings by Patañjali, corresponding to the activities of the ordinary mind, namely, pramana (judging, comparing, discursive activity), viparyaya (misjudging, misperception), vikalpa (verbal association, imagination), nidra (dreaming, sleeping), and smriti (memory arising from past experience).

According to an underlying assumption of yoga, the mind, which is confined to the above modes, is limited in scope and cannot know the objective truth about anything. The mind is not the true knower: it can infer or quote authority or make hypotheses or speculate about the nature of reality, but it cannot see objects directly—from the inside, as it were, as they really are in themselves. In order to allow direct seeing to take place, the mind, which by its very nature attempts to mediate between the object and the subject, has to be quieted. When the mind is totally silent and totally alert, both the subject (purusha) and the object (prakriti) are simultaneously present to it: the seer is there; what is to be seen is there; and the seeing takes place without distortion. Then there is no comparing or judging, no misunderstanding, no fantasizing, no dozing off in heedlessness, nor any clinging to past knowledge. There is simply the seeing. That state is called kaivalya (literally, aloneness). It is not the aloneness of the seer separated from the seen, as is unfortunately far too often maintained as a goal of yoga, but the aloneness of seeing in its purity, without any distortions introduced by the organs of perception, namely, the mind, the heart, and the senses. The aim of yoga is clear seeing, which is the sole power of the seer (YS 2.20) and only of the seer (purusha), not of the mind.

It is of utmost importance, from the point of view of yoga, to distinguish between the mind (chitta) and the real seer (purusha). Chitta pretends to know, but it is in the realm of the known and the seen. The misidentification between the seer (subject) and the seen (object)—which is mistaking chitta with its fluctuations and its sorrows for purusha, which is without sorrow and without alterations—is the fundamental error from which all other problems and suffering arise (YS 3.17). This basic ignorance is what gives rise to asmita (I-am-this-ness or egoism). This is a limitation by particularization: purusha says “I am”; asmita says “I am this” or “I am that.” The strong desire to perpetuate the personal self and the resulting separation from all else, which manifests as a wish for continuation (abhinivesha) of this separate entity, comes from this egoism. This wish is maintained by indulging in “I-like-this” (raga, attraction) or “I-do-not-like-this” (dvesha, aversion). Freedom from the fundamental ignorance leading to all sorrow is achieved by an unceasing vision of discernment (viveka-khyati). This vision of discernment alone can permit transcendental insight (prajña) to arise. Nothing can force the appearance of this insight; all one can do is to prepare the ground for it. Since it is said that the whole purpose for the existence of the mind as well as the rest of prakriti is to serve purusha, if the ground is properly prepared, prajña is likely to arise.

The ground to be prepared is the entire psychosomatic organism, sharira, for it is through the whole organism that purusha sees and prajña arises, not the mind alone nor the heart nor the physical body by itself. One with dulled senses has as little chance of coming to prajña as one with a stupid mind or with an unfeeling heart. Agitation in any part of the entire organism causes a fluctuation of attention. And every act, including mental acts like thought, volition, and intention, leaves an impression (samskara) on the psyche, which in turn lodges itself in the various tensions, postures, and gestures of the physical body. These impressions in turn create tendencies (vasana) which dispose one toward certain sorts of actions.

The really deep tendencies cut across the boundaries of what we ordinarily call life and death—that is, the life and death of the physical body. This, in short, is the law of karma (action, work): as one acts, so one becomes; and as one is, so one acts. It is less to say that one reaps what one sows; it is more to say, in accordance with the ideas of yoga, that every act makes a person a little different from before, and this different person now naturally acts according to the tendencies of the new being. Within the realm of prakriti and karma, a person is not anything except their actions, thoughts, feelings, and all the conditioning of the past. A person is an expression of the working out of the law of karma. One repeats oneself helplessly, at the same level, neurotically, precisely because one does not know what one does and why. But just as there is a cosmic tendency for this mechanical repetition (pravritti), there is also a cosmic tendency for waking up to our real situation (nivritti) which can free us from a repetition of the past.

The effort required, with the ultimate aim of coming to the vision of discernment (viveka-khayati), which alone may lead to true insight (prajña), is enormously difficult, for the simple reason that a total cleansing of the deepest recesses of our entire consciousness is required. Otherwise, subtle impressions and tendencies will reassert themselves, leading us into a repetitious circle. What is needed is a flow (pratiprasava) counter to the ordinary tendencies of prakriti, a turning around (metanoia in Greek, usually translated as ‘repentance’ in the New Testament).

It is only by a reversal of the usual tendencies of the mind that its agitations can be quietened. Then the mind can know its right and proper place with respect to the purusha, as the known rather than the knower (YS 2.10; 4.18–22). However pure and refined the mind is, in the terminology of the Yoga Sutra, even if the mind is constituted of pure satva (luminosity, purity), it is distinct from purusha and is radically inferior to it in its power of seeing.

The Limbs of Yoga

The usual tendencies of the mind are countered through the eight limbs of Yoga by steady practice (abhyasa) and increasing inwardness (vairagya). Elsewhere, in YS 2.1–2, a different scheme is indicated: austerity, self-study, and devotion to Ishvara (the Lord) constitute Kriya yoga, which has as its purpose the lessening of the causes-of-sorrow (kleshas) and the cultivation of samadhi (settled intelligence, silence). Here we shall follow the much more elaborated scheme (YS 2.28–55; 3.1–8) of the eight limbs: yama, niyama, asana, pranayama, pratyahara, dharana, dhyana, and samadhi. The first one, yama, refers to the various self-restraints, which include abstention from violence, falsehood, theft, incontinence, and acquisitiveness. The second limb, niyama, consists in the observances of purity, contentment, austerity, self-study, and devotion to Ishvara. (These last three observances are the same that were said earlier to constitute kriya yoga). The third and fourth limbs, asana and pranayama, are concerned with the right posture, which makes one both relaxed and alert, and with the proper regulation of breathing for steadying the attention. These two limbs by themselves are often elaborated in terms of numerous postures and breathing exercises in schools of hatha yoga, the yoga of force. In the physical culture aspect of yoga, sometimes one encounters great displays of ascetic prowess, which have nothing to do with the purpose of yoga.

The fifth limb, pratyahara, is the inward turning of the senses so that they can be freed of the external impressions in order to obey the mind. These five limbs constitute the outer group from the total eight limbs of yoga, the other three being the more inner limbs. Dharana is concentration in which the consciousness is bound to a single spot; dhyana is contemplation or meditative absorption in which there is an uninterrupted flow of attention from the observer to the observed. So far the observer has acted as the center of consciousness which sees. When the observing is done by purusha, through the mind emptied of itself, that state is called samadhi, a state of silence and of settled intelligence.

In this state the mind does not introduce its own distortions, and the object can be known truly, as it is. This is an inversion of the usual mode of knowing, in which the mind receives the impressions about the object from the senses and imposes its own fluctuations (vrittis) upon the object. In samadhi, the mind acts as the arena in which there is no subjective or personal center of consciousness that can introduce any distortion of the object; there is only the pure seeing. No agency or organ mediates between the object and the seeing. Thus, the insight obtained in the state of samadhi is neither sensual nor mental, nor has it to do with feelings. It is not personal knowledge, nor is it subjective. It refers wholly and exclusively to the object; it is completely objective insight—of the object as it is and as it chooses to reveal itself, without any violation or forcing from the observer—for, at the moment of pure seeing, the observer as a separated center of consciousness does not exist. As the Yoga Sutra says (1.48–49; 2.15; 3.54), the insight in the state of samadhi is truth-bearing (ritambhara). The scope of this insight is different from the scope of the knowledge gained from tradition or inference. Unlike the latter knowledge, the insight of prajña reveals the unique particularity, rather than an abstract generality, of the object. For this reason, mystical insight is often considered closer to sense perception rather than discursive knowledge; it is clear, however, that in prajña the senses are extremely refined and turned inward and do not mediate between the seer and the object.

Unlike mental knowledge, in which there is an opposition between the object and the modalities of the mind, an opposition that inevitably leads to sorrow, the insight of prajña, born of a sustained vision of discernment, is said to be the deliverer. Prajña can pertain to any object, large or small, far or near, and to any time, past, present or future, for it is without time sequence, present everywhere at once.

It may be remarked that the various steps of yoga are ordered yet are not sequentially linear. The completion of one step is not required before the next one can be undertaken. Some of the apparent linearity arises from the analytical and linguistic nature of the exposition. Earlier steps are preparatory to the later ones, but they are not absolutely necessary. Nor are they completely sufficient, for they do not determine the later steps. A right physical posture or moral conduct may aid internal development but it does not guarantee it. More often, the external behavior reflects the internal development. As an example, a person does not necessarily become wise by breathing or thinking in a particular way; a person breathes and thinks in that way because of their level of wisdom.

The three inner limbs of yoga, namely, dharana, dhyana, and samadhi, together constitute what is called samyama (discipline, constraint). It is the application of samyama to any object which leads to the direct perception (sakshatkara) of it because in the state of quietude in which the vrittis are removed, the chitta is like a transparent jewel taking on the true color of the object which fuses (samapatti) with it (YS 1.41). The special attention which prevails in the state of samyama can be brought to bear on any aspect of prakriti, which, as was said earlier, encompasses all that can be an object of perception, however subtle.

The basic research method of the natural science of yoga is to bring a completely quiet mind and to wait without agitation or projection, letting the object reveal itself in its own true nature. This science is further extended by the principles of analogy and isomorphism between the macrocosmos and the microcosmos which is the human organism. A particularly striking example of this isomorphism is to be found in the Yoga Darshana Upanishad, where the external mountains and other places are identified with the various parts of the organism. The external tirtha (sacred ford, holy water, place of pilgrimage) is considered inferior to the tirtha in the body.

The Mount Meru is in the head and Kedara in your brow; between your eyebrows, near your nose, know, dear disciple, that Varanasi stands; in your heart is the confluence of the Ganges and the Yamuna; lastly, Kamalalya is to be found in the muladhara, To prefer external tirthas to those concealed in your body, is to prefer common potsherds to diamonds laid in your hands. Your sins will be washed away, whether you have made love with your wife or even with your own daughter, if you carry out the pilgrimages within your own body from one tirtha to another. True yogis who worship the atman in themselves have no need of water tirthas or of gods of wood and clay. The tirthas of your body infinitely surpass those of the world, and the tirtha-of-the-soul is the greatest of them: the others are nothing beside it.

—Yoga Darshana Upanishad (4.48–53)

Yoga and Power

A large number of aphorisms in the Yoga Sutra (3.16–53) describe the knowledge and the powers gained by attending to various objects in the state of samyama. For example, we are told that through samyama on the sun, one gains insight into the solar system, and by samyama on the moon, knowledge of the arrangement of the stars (YS 3.26–27). Similarly, many occult or extraordinary powers, siddhis, accrue to the yogi by bringing the state of samyama to bear on various aspects of oneself: for example, by samyama on the relation between the ear and ether, one acquires the divine ear by which one can hear at a distance or hear extremely subtle and usually inaudible sounds. Many other powers are mentioned by Patañjali; however, none of them is his main concern. These powers may be present from birth or they may be acquired by other means such as drugs or mantras (literally, ‘mind-instrument’; special sounds usually given by a teacher to the disciple for recitation) or physical austerities (YS 4.1).

There is no suggestion that there is anything wrong with these powers, nor is there a suggestion that there is anything wrong with the mind as it is. The point is more that the mind, as it is, is an inadequate instrument for true knowledge; similarly, these powers, however vast, are inadequate as the goal of true knowledge. The yogis who get preoccupied with them are likely to get sidetracked from the true path of yoga. Therefore, these powers are seen as temptations and, along with heightened sensory experiences, are regarded as obstacles to sustained samadhi (YS 3.36–37).

The Spirituality of Yoga Discipline

The real seer is purusha, which is not personally mine or yours; it is the pure power of seeing. In yoga, as a continuation of the Vedic sacrifice (yajña), the sacrifice of the limiting mind is required for the sake of an unlimited power to see. Sacrifice of the separated self, with all of its fears and hopes, likes and dislikes, sorrows and pleasures, failures and ambitions is needed for the sake of the Only One who truly sees. Then the sacrifice of the seen for the sake of the Only One who truly is follows. This comes about in nirbija samadhi (seedless silence), when there is no object separated from the purusha, there is no subject separated from the purusha, there is no knowing except the purusha. The seer, the seen, and the seeing are all One; there is no other. This is the state of kaivalya, of aloneness, not because there is an opposition or a separation but simply because there is no other. With respect to this state of samadhi, the previously labeled inner limbs of yoga are also outer. This samadhi is also called dharmamegha-samadhi(silence in the cloud of right order). Thence follows the ending of all the causes of sorrow, of all the blemishes and imperfections; little remains to be known, for the insight in this state is infinite; the purpose of the human incarnation is fulfilled and the yogi is completely free and established in the pure awareness of purusha (YS 4.29–34).

In this movement from the personal self to the Self, from the identification with chitta to the identification with purusha, right internal order is established. The sacrifice (from the Latin sacre facere, ‘to make sacred’) of chitta and prakriti for the sake of purusha is precisely what renders them sacred and gives them significance. In this process of transformation, many stages and their corresponding levels of silence are described in the Yoga Sutra. As a whole, the process of yoga allows the emergence of purusha from within the psychosomatic organism, as a sculpture is released from the stone by chiseling and discarding. The organism, or prakriti in general, is no more an impediment to purusha than the stone is to the sculpture. Nor is prakriti considered unreal or a mental projection. Everything in prakriti is considered as alive: she is very real, and though she can overwhelm the mind with her dynamism and charms and veil the truth, yet in her proper place and function she exists in order to serve purusha.

The discipline of yoga is against the ordinary current. All the eight limbs of yoga place constraints on the usual activity of our desires, inclinations, body, breath, senses, mind, attention, and ego, so that they may be brought under the control of something higher. The more controlled and quieted these various aspects of ourselves are, the greater is the development of the vision of discernment. This, in its turn, leads to the removal of ignorance about our true identity. Then we realize that we have been identifying ourselves only with our mental-physical self, which is of the nature of the object rather than the real seer. When this misidentification is broken and we no longer rely on the mind for true insight, the natural conflict between the whole and the part—that is, between what is and the projections of the mind—is dissolved. This leads to the removal of sorrow and its underlying causes, and to the cultivation of a deeper and deeper silence, and finally to the aloneness of pure awareness.

Many Yogas

What we have described so far is the classical and central yoga, sometimes called the raja Yoga (the Royal Yoga). Kriya-yoga, noted in the Yoga Sutra (YS 2.1–2), which consists of austerity, self-study, and devotion to the Lord; and hatha yoga, which focuses on the physical culture aspect of yoga and concentrates on the asanas and pranayama, have also been briefly discussed. Many other different forms of yoga have been developed with different emphases or exaggerations of one aspect or another. For example, Patañjali mentions (YS 1.29–40) that inwardness can be cultivated and the distractions of the mind attenuated by the practice of concentration on a single principle, or by the projection of friendliness, compassion, and equanimity toward others, or by the appropriate retention and expulsion of breath, or by dwelling on those who have conquered attachment, or by attending to inner sensations. Corresponding to each one of these possible techniques, whole schools have arisen which cultivate one or the other method, which can be called a specific yoga. Over time, yoga has thus come to stand for any spiritual path, method, or technique—although, in general, the goal of all these yogas is the same as that of the central yoga, even when expressed in terms of the particular metaphysics and metaphors of their own schools.

Owing to the multifarious uses to which the word ‘yoga’ can be and has been put, no exhaustive list of all the yogas can be given. Among the well-known varieties are mantra yoga, which makes use of the recitation of special sounds usually given by a teacher to a disciple; laya yoga, in which one makes use of the inner sound for merging the mind into the infinite; kundalini yoga, which describes the whole process of yoga in terms of wakening the cosmic energy usually lying dormant coiled up at the base of the spine, so that it can rise through the various centers (chakra) in the subtle body, and the various yogas mentioned and elaborated in the Bhagavad Gita. The theory and the practice of kundalini yoga have been much developed in the Tantric literature, describing in detail the movements and transformation of the energies (shakti) in the body.

The Bhagavad Gita expands the use of the word ‘yoga’ enormously. In addition to the well-known yogas called karma yoga (yoga of action), bhakti yoga (yoga of love and devotion), and jñana yoga (yoga of knowledge), every chapter in the Bhagavad Gita ends with a colophon labeling it a yoga. For example, the first chapter ends with the colophon (not perhaps found in the earlier texts) calling it “The Yoga of Arjuna’s Confusion,” and the eleventh chapter is called “The Yoga of the Vision of Cosmic Form,” and so on. Anything that can be made use of and harmonized with the general principles of yoga in the quest for a connection with the Absolute can be called a specific sort of yoga.

Three further remarks can be made here about the Bhagavad Gita. First, the Bhagavad Gita is absolutely essential for an understanding of yoga; it is a text par excellence on yoga, as is the Yoga Sutra. Second, the Bhagavad Gita extends the range and understanding of yoga in at least two different ways. By forging a link between classical yoga and other metaphysical systems and metaphors, it enlarges our vision of the scope of yoga. We are reminded by the whole setting of the battlefield, by the insistence on action in this world of prakriti, and by the presence of Krishna himself as a model yogi, that not only is there no conflict between prakriti and purusha but that, rightly seen, prakriti can and does serve the purposes of purusha. Furthermore, a free purusha, as exemplified by Krishna, acts in prakriti not from compulsion but from freedom and compassion, as and when there is a need for it.

Third, the central yoga that Krishna teaches in the Bhagavad Gita is buddhi yoga (the yoga of integrated intelligence and discernment), of which the various aspects are yogas such as karma yoga, bhakti yoga, and jñana yoga. The place of buddhi in the Bhagavad Gita is central. Krishna advises Arjuna to “seek refuge in buddhi” (BG 2.49). “To them who are constantly integrated worshiping me with love, I give that buddhi yoga by which they may draw near to me” (BG 10.10). Later, during the process of summing up his entire teaching, Krishna says again, “Renouncing all actions to me, making me your goal, relying on buddhi yoga, become constantly mindful of me. Mindful of me you will overcome all obstacles by my grace. But if because of self-centeredness you will not listen, you will perish” (BG 18.57–58). It is only the integrated buddhi which can have a vision of and follow dictates of purusha. Buddhi is what gives a focus to an integral yoga, for example, of the sort elaborated by Sri Aurobindo in the twentieth century, very much under the influence of the Bhagavad Gita. This is what corresponds precisely to the vivekakhyati (vision of discernment) in the Yoga Sutra by which alone the root ignorance can be removed.

Right Order

That which the yogis seek does not serve their own purposes. In fact, as long as we have our own purposes, we cannot really be open to higher and sacred purposes. The whole meaning of yoga can be understood as progressive freedom from the hindrances that impede our availability to the purposes of the suprapersonal intelligence. The major hindrance is what we usually call our ego or self; as long as it serves its own ends, it cannot serve the ends of the real Self.

What yoga aims at is right internal order, which is primarily vertical. Yoga takes its direction and significance from the reality that is beyond the body or the psyche. This is what renders the physio-psychology of yoga sacred. Cultivation of the body or the mind for its own sake is not yoga. The psychic healing in yoga has its center above the psyche; here the wholeness aspired to is that of holiness. Normal physical and psychological functioning is necessary but not sufficient; without the movement along the vertical spiritual axis, any adjustment in the psyche constitutes only a horizontal arrangement of subtle matter. It is the stillness of the psyche that is required so that the purusha may be heard and may hear. Patañjali had defined yoga, in terms of its procedure, as the controlling of the fluctuations of consciousness (chitta); Vyasa, in his commentary on the Yoga Sutra (Yoga Bhashya 1.1) defines yoga in terms of its aim as silence (samadhi). Then purusha abides in his own true form.

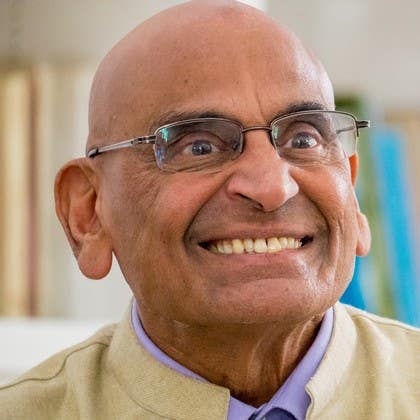

Excerpted from Spiritual Roots of Yoga by Ravi Ravindra (Morning Light Press, Sandpoint ID, 2006) {This article is based on “Yoga: The Royal Path to Freedom” in Hindu Spirituality: Vedas through Vedanta. ed. K. Sivaraman (New York: Crossroad Publishers, 1989). Vol. 6 of World Spirituality: An Encyclopedic History of the Religious Quest.]

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!

You need to be a subscriber to post a comment.

Please Log In or Create an Account to start your free trial.