Description

About This Video

Transcript

Read Full Transcript

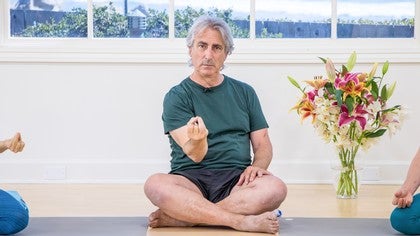

Hi, we're here with Betsy and Alana, and we're working on Jalandara Bandha. Jala means net, actually. It's often been confused with the word water, but it means net. Jalandara means to hold, and so Jalandara means the net holding lock or bond or valve, as I prefer it. What they're referring to is the network of nadis in the throat.

I don't really favor the name Jalandara Bandha. I much prefer to call it Kanta Bandha, which makes it more direct. Kanta simply means throat, but the more popular name for it is Jalandara. This is one of the three major Bandhas that are used during the practice of Pranayama. Now, a Bandha is a subset of the Mudras, and they'll always be listed together.

Bandha is cognate with the English word bond. The other two major Bandhas are, of course, Mula Bandha, which is the contraction of the perineal muscles, and Udayana Bandha, which is the contraction of the rectus muscles. The idea behind that is that the torso is a container, is a pot, is a kumbha, which is where we get the word kumbhaka from, which literally means pot-like. And the idea then is to seal off the two openings in the pot, the throat and the anus, by using these locks, to be able to contain the pranayama inside the torso. But there are really two reasons for doing a kumbhaka.

There's two different schools of pranayama, in other words. Number one is classical yoga, which is, of course, based on the yoga sutra, attributed to Patanjali. And in that practice, pranayama is simply a means of slowing the breath down, until it becomes really slow or stops completely. There's nothing else going on in that form of practice, as far as pranayama is concerned. If you have read that text, and remember the famous second sutra in the first chapter, yoga is the restriction of fluctuations of consciousness.

The fluctuations, of course, start with the body, and that's why you perform an asana, steady and comfortable, to cut down on the fidgeting of the body. And then, of course, breathing is also a movement, inhale, exhale. So the pranayama in that school is simply a means of slowing down the fluctuations of the physical body, which will, in turn, quiet the mind. The other pranayama model is from Hatha Yoga. It's a bit more complicated to explain why you want to do that, but it involves stimulating the dormant physical energy, which in that school of yogas, known as kundalini, kundala, is the coiled one, which is the potential energy that's stored at the base of the spine.

We are going to pretend that we are doing the first practice of just simply slowing down the breath in preparation for meditation, which is what classical yoga is all about. And in doing that, we're going to work on jala nirabhanda. We don't particularly want to work on mula bandha and udiyana bandha without having an experienced teacher watching you do that. Jala nirabhanda is okay to do, but the other two are not particularly simple and can be a little bit difficult at times, so you really want to be careful with the latter two of those practices. And we've done the preparation for jala nirabhanda, and we've made the point that it's not so much that you bring the chin down to the sternum, you want to bring the sternum up to the chin, ideally.

And in order to do that, the first thing you do is to boost the top of the sternum bone, and we did an exercise to teach ourselves how to do that. It's initiated from the base of the skull, which pulls up on the manubrium, and from the lower tips of the shoulder blades, which push up from below. So the sternum is lifted from above and boosted from below. So our helpers are sitting in preparation for that, and they're simply observing their breathing right now as we do to start any pranayama practice. Prana, by the way, is usually translated as vital energy or breath or something like that.

Literally, it means to breathe forth. Prah means to come forward, like prakriti. An an is a verb means to breathe, and it's cognate with English words like animate and animal. Ayama is a word that means to hold and to extend. So pranayama literally means to hold onto and then extend or expand the breathing forth.

So let's observe the breath, and what we'll do is we'll start very slowly to segue into ujjayi pranayama. So we'll slow the breathing down a bit, and we'll start to create that sound at the back of the throat that we learned how to do earlier, what we were calling the ajapa mantra or the hamsa mantra, depending on how you look at it. The idea behind those names is that what the yogis are trying to relay to us is that the breath is a bridge between the mundane world and the spiritual, and it's a way for us to contact the spirit or the soul. So we're slowing the breath down, and in particular the exhalations. Typically, in a breathing practice like this, the exhalations are twice as long as the inhalations.

So for every one count of inhale that we take, we're supposed to take two counts of exhale. That's a common ratio. There are other ratios that you can find in the older texts, but most commonly the ratio is one to two, one count of inhale, two counts of exhale. So for example, if you're inhaling for four counts, you'll also want to then exhale for eight counts if you're following that ratio. Now the ratios for the retentions in hata yoga anyway are fairly rigorous, and I'm not going to ask our helpers today to do that.

We're going to take it a little bit more conservatively. I think it's very important to do things slowly and carefully with your breath and not push things too fast, too soon. So let's get our helpers to do something that's called, in the modern yoga, samavritti pranayama. Sama means sane or equal, and vritti in this context means ratio. So I'm going to ask them to take an exhalation and then begin to inhale and count, om one, om two, om three, om four, and then I want them to exhale, om one, om two, om three, om four. Now this is probably not long enough. They'll feel a little bit rushed with the breath at this count, but I'd like to start out with a rather lower count. They work the way up.

So we'll coordinate the inhalations and exhalations with that four count, and we'll see how that goes for a few cycles. And then at some point, if you feel that you can do a bit more, then we'll do om one, two, three, four, five, inhale, om one, two, three, four, five, exhale. And we'll do a few more cycles like that. Very nice. And then if you're still feeling relatively comfortable, we'll go to six and so on and so forth. Now, this is not an Olympic event, so you're not trying to go as high as you can.

You're trying to find a number that you're very comfortable with. And again, this is the way that modern yogis begin their practice with samavritti. When the ratios are one to two, it's called vishamavritti, the unequal ratio. So we'll give them a little bit more time to get themselves to find that number that they like as far as their breathing is concerned. And then what I'm going to ask them to do is to take that number, whatever it is, let's say it's six, and cut it in half.

So let me see that half is six, I believe would be three. And if it's an odd number, I want them to go down a little bit lower. So if it's five, I want you to go down to two. And then I would like you to take an inhalation to whatever number that you're using. And as you're near the end of that breath, that inhalation, lift the base of the skull away from the back of the neck, twist the lower tips of the shoulder blades up toward the top of the sternum, take the top of the sternum bone up, and very gently bring the chin down over the crook of the throat.

Now remember, it's not that you're bringing the chin down, it's more like you're swiveling the head over the crook of the throat. And I want you to hold the breath for that number that you're using, whether it's three or two or whatever it is. At the end of the hold, it's going to be very brief, exhale out through the nose, keeping the head down. And then at the end of that exhalation, bring the head up back into a neutral position. And take one or two or even three regular breaths.

And then we'll try again. Inhale to your count, whatever that happens to be. And once again, as you near the end of that inhalation, start to lift the top of the sternum bone. And then the chin swivels so the crook of the throat should feel as if it's moving more deeply into the head toward the atlas at the top of the spine. Imagine that you're doing a forward bend, and that your head is the torso, and that the crook of the throat are your groins.

So that you're sharpening the groins, bringing the torso down over the groins onto the thighs. But the groins stay soft, or in this case the crook of the throat. Hold for whatever number that you're using, exhale through the nose, and then bring the head up. Inhale. Back into a neutral position.

Take again one or two or even three regular breaths. And we'll go one more time. This is kumbaka in preparation for meditation. One more time. Inhale, and then down you go.

Or up you go, maybe I should say. So as you may remember from the classical system, the next stage after pranayama is called pratyahara. And we are eventually going to work on a pratyahara practice that comes from hatha yoga, called drawing down the wind. And then exhale through the nose, bring the head up. When I see done, take a few breaths, well done.

And then let's try that shrug the shoulder again and see if we can't let those shoulders drop into gravity rather than being pulled down. Ah, now it's happening. Very nice. This is jalandharabhandha, which is a very important exercise for kumbaka. And kumbaka then is retention, literally remember kumbaka means pot-like, which is a reference to the torso in which the prana is being retained.

Thank you.

Pranayama & Meditation: Meet Your Breath

Comments

You need to be a subscriber to post a comment.

Please Log In or Create an Account to start your free trial.